In the last three volumes of our Powerful Writing Series, we laid out the case that compelling writing often hinges on mastering the formulas—even the sleights of hand—within the text itself just as much as it relies on the writer’s talent. (We also urged you to watch Moonstruck, and we confess that whatever happened to Nicolas Cage’s career baffles us, as well.)

This fourth installment of our series will highlight a few more of the elements of style that writers draw on to structure their vision and stencil forth the contours of their imagination. Think of the sections that follow as recommendations—rather than rules—that may help you arrange your words in such a way that (to paraphrase E. B. White) they ignite in your reader’s mind.

Write in Verbs and Nouns

Verbs and nouns are the hammers and nails of language, while adjectives and adverbs are the paint and varnish. A sentence of verbs and nouns feels hard-won, and it says more with less.

Few writers in the US have wielded verbs and nouns with the same force as Breece D’J Pancake—a writer from West Virginia who killed himself when he was 26. The slim volume of stories that Pancake left behind established him as something akin to the Good Will Hunting of American lit. Prepare for his description of daybreak in a small town to leave you breathless:

Daylight fires the ridges green, shifts the colors of the fog, touches the brick streets of Rock Camp with a reddish tone. The streetlights flicker out, and the traffic signal at the far end of Front Street’s yoke snaps on; stopping nothing, warning nothing, rushing nothing on.

Pancake could’ve written “The green ridges are sunny” or “The red streets are foggy” or “The traffic signal comes on suddenly.” But the verbs he chose energize the writing—“Daylight fires the ridges green, shifts the colors of the fog, touches the brick streets …”—animating a few lines about wisps of morning air with a vivid sense of place.

Adjectives and adverbs aren’t your enemies, per se, but they do tend to be decorative rather than distilled. Still, as we wrote in volume 3 of our series, “Good writing follows the rules. Great writing is when you know how to break them.” Consider this passage from Robert Louis Stevenson’s Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, in which one of Jekyll’s friends vows to track down Hyde:

From that time forward, Mr. Utterson began to haunt the door in the by-street of shops. In the morning before office hours, at noon when business was plenty, and time scarce, at night under the face of the fogged city moon, by all lights and at all hours of solitude or concourse, the lawyer was to be found on his chosen post.

Stevenson could’ve crunched the phrase “fogged city moon” down to “Fog wreathed the moon.” That line, revised with hard-hitting brevity, fulfills our verbs-and-noun maxim. But “under the face of the fogged city moon” conjures up images of a moon floating above the charred chimney-pots of Victorian London—and in a voice that flows so hypnotically that to make it more compact might drain it of its dark seductiveness.

Why Should You Care?

Reading overwrought prose can be the mental equivalent of gorging on a calorie bomb—so saccharine that you want to spit it out. Phrases embedded with adjectives (“We serve delicious meals to happy customers who love our best-in-class service”) have about them an air of desperation, while sentences built on verbs and nouns convey a sincerity that should help to win your audience over.

Repeat Yourself

Once again this year, high school students all over this country will have this lesson drilled into them: Never repeat words in the same sentence. Granted, you could be more original than crafting a narrative description like this: “He went to his room and opened his closet. He looked inside his closet. There was nothing in his closet. He closed the closet door again.” Yet, handled adroitly, repetition frees the rhythm inside your words.

Some of our best-known idioms have stayed with us for centuries because they repeat words. Take this one: “The longest way round is the shortest way home.” “Way” appears twice in quick succession, but changing it to “The longest way round is the shortest direction home” saps it of its bouncing vigor. “The longest way round is the shortest route home” nearly works—“round” and “route” nod to each other—except the wisdom of the line now sounds flat and technical.

In King Lear, when Lear rages upon the storm-blasted heath, one of his banished counselors, Kent, laments that the old mad king wanders beneath the “wrathful skies” and “horrid thunder”:

Alas, sir, are you here? things that love night

Love not such nights as these.

That line calls up pictures of wolves huddling in dens or owls shivering within sopping branches. Writers taught to fear and loath repetition might be alarmed that “love” and “night” crop up twice so close together, and feel compelled to lobotomize that line:

Alas, sir, are you here? things that love night

Do not enjoy being outdoors in inclement weather.

Yes, that edit adheres to the thou-shalt-not-repeat-thyself rule—but at what cost? A passage that was mysterious and sensuous now feels like a ping from weather.com.

Why Should You Care?

A single word, poorly placed, can kill a sentence, a headline, a pitch to a client. None of us sound smarter writing with a thesaurus opened up next to us. Listen for the cadence in your writing and trust your ear to tell you when to vary up your vocab or say what you mean directly—no matter if you say the same word twice.

Break Necks and Feint Jabs

All these principles of composition apply to the everyday tasks of copywriters, who are called on to write countless headlines throughout their careers. So it’s worth noting that the pun is the lowest form of headline. We don’t mean a Dickenian pun, a triple entendre, a timeless witticism. No, no—think “Have a Beary Good Day” tchotchkes hanging in the cabin in the woods that you found on AirBNB. A step above the pun is an approach to headlines that might be termed “Break a cliche’s neck.” Case in point: This ad from The Economist.

The angle here is that The Economist is for the cognoscenti, the discerning reader, someone so well-informed that she can eviscerate the rest of the debate team when the subject of current affairs arises. Ergo, the writer took a well-worn saying (“Drink someone under the table”), switched out the first word, and—presto!—you’ve got a headline reinvigorated with confidence.

Clever enough, but breaking cliches’ necks can sometimes turn into a game of flipping Solo cups over to see which one’s covering the ping-pong ball. A related—and somewhat more elevated—technique is the feint-jab sentence, which Oscar Wilde is the master of. Behold this Wilde quote:

Always forgive your enemies; nothing annoys them so much.

The first part of the sentence, pre-semi-colon, is a distraction meant to catch you off guard so he can knock you back with the second part. The man left behind him scads of such quotes, which still have enough snarky bite to lead an ad campaign today:

- I can resist everything except temptation.

- Everything in moderation, including moderation.

- I have the simplest of tastes. I am always satisfied with the best.

- I can never travel without my diary. One should always have something sensational to read on the train.

On and on, this guy—feint, jab, feint, jab. Yet we delight in Wilde’s charm, even as it pummels us, and that’s the point: Anything that makes us laugh out loud is probably a stellar headline.

Why Should You Care?

Depending on what you’re selling or where you’re publishing, your audience might want vastly different things. But plenty of audiences love to blush, belly laugh, howl with glee. Lines that surprise and delight them will grab their attention and sustain it for years.

Trust Your Insights

Earlier we said that the lowest form of headline is the pun. In our view, the highest form of headline is an insight.

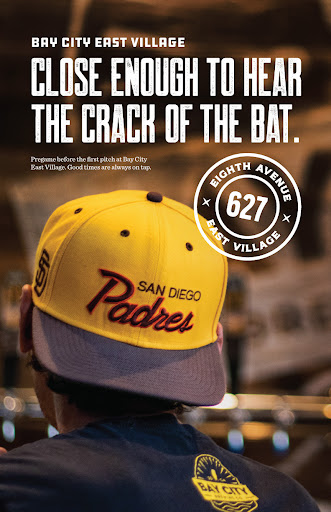

We’re located in downtown San Diego, and we share our rooftop with one of our clients—Bay City Brewing. One of the selling-points of Bay City is that they’re a few blocks north of Petco Park, where the Padres play. Here’s an ad we wrote for them a few weeks back.

“Close enough to hear the crack of the bat” felt like the perfect headline for Bay City because they’re—well, they’re close enough to Petco Park to hear the crack of the bat.

Conclusion

So much of copywriting relies on the switcheroo, the 1-2 punch, the other tips and tricks you pick up along the way. But beneath all the patterns is chaos, and the best writing is finally a flash of power, where the writer gets out of the way and draws from the soul, arranging words so that, within the reader’s mind, they explode.